Eat, Love, Pray the Roman Way: Fortuna at Praeneste

Palestrina has definitely seen better times. Today it is – on the surface – a rather nondescript (if not rough) Italian country town of some 20000 inhabitants in the foothills of the Appenin mountain range about 35 km East of Rome.

Back in the days of the Roman empire, Praeneste, as it was known then, was a luxury resort town for the rich and famous of imperial society who built their villas in the area to take advantage of Praeneste’s cool microclimate. Elevated at 450 meters above sea level and subjected to cooling winds from the ocean and vast plain below, Praeneste used to be a popular summer resort. Great emperors like Augustus and Marcus Aurelius spent time here and Hadrian even maintained a villa in Praeneste. Aristocrat and historian Pliny the Younger who came to fame in our time through his accurate description of pyroclastic flows during the eruption of Vesuvius that buried Pompeii and Herculaneum also owned a villa here.

The focal point of Praeneste in antiquity was, however, its vast Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia temple complex dedicated to Fortuna, the Roman goddess of luck and its associated (human) oracle through which believers would talk to the goddess. The largest sanctuary in the empire (maybe with the exception of Egypt) could be seen from as far as Rome on clear days and was certainly in good sight of the ancient south- and eastbound ‘freeways’, the Via Praenestina and the Via Labicana. Praeneste and the sanctuary were something of an early tourist attraction, a bustling, prosperous fun town where residents and visitors enjoyed gladiatorial games, baths and markets and – unusually – two fora (functional town centers). As we will see, this town of life and pleasure left behind many witnesses to everyday life in fabulous Rome whose sophistication fascinates us to this day.

A 2200-year-old masterpiece of Roman concrete architecture

First there is the structure of the sanctuary itself which incidentally was only rediscovered after US bombers in WWII had blasted away all the houses which had overgrown the ruins of the Roman sanctuary. Keep in mind that the Western part of the Roman empire collapsed in the 5th century while the complex was probably constructed in the 2nd century BC which gave the successors to Rome’s rule a whopping 1700 years to take the structure apart.

Yet, Roman concrete is known to be tough and when you drive by or walk through the sanctuary today, you could easily think that the ruins are just about contemporary. The overall layout of the sanctuary has been largely preserved. The Romans basically terraced – and thereby transformed – the entire mountain side and re-enforced their construction with concrete and the usual maze of collonades, arches and vaults. Keeping with Roman architectural traditions the structure is open and focused at the same time. Visitors can access from the left or right through sloped ramps at the bottom of the sanctuary, but only advance to the next level after returning to the central stairway. This repeats itself on all five levels. You can walk around left and right, but you have to return to the stairs to go up. The actual temple of Fortuna is a small round building at the apex of the sanctuary.

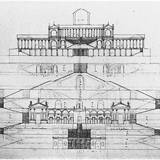

Model of the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia in Palestrina near Rome

So far, so good. A key takeaway is the astonishing longevity of the sanctuary’s influence on the architecture of buildings and particularly gardens built on steep slopes not only during antiquity, but also reaching into the age of the renaissance (14th to 17th century AD) and beyond. A celebrated example are the world famous water gardens at the Villa d’Este in Tivoli due East of Rome. Carved into a hillside, both the ascent to the palatial villa and some of the giant fountains are organized in the ramp-stairs scheme of Fortuna’s Sanctuary. Another grand, but recent landmark in Rome, heavily influenced by the Sanctuary is the Vittorio Emanuele II monument (to the first king of modern Italy), at the Capitoline Hill in central Rome. By the way, when in the area, climb up to the viewing platform on top of the monument (using the elevator for the last leg) to enjoy some on the most memorable views of Rome.

- Pleasant view towards the Castelli Romani and Pomezia from the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia in Palestrina, Italy

- Sketch of how Andrea Palladio imagined the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia to have looked like in Roman times

- Vittorio Emanuele II monument in Rome, Italy

- Fountain of Neptune at Villa d’Este in Tivoli, near Rome

- Villa d’Este in Tivoli, Rome, in the 16th century; by Étienne Dupérac

- Model of the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia at Palestrina, Italy

Apart from the role the sanctuary has played in the history of architecture in the Western world, there are plenty of smaller points of interest. For example the sheer scale and brazenness of the construction. Keep in mind that it was erected 2200 years ago. This was a civilization without confidence problems. It built the impossible – and had excellent taste at that. The view from the top levels of the sanctuary is sublime and although it is today a little hard to imagine, looking at the reconstruction of the sanctuary (photo series below), you can picture the pleasure of walking through its symphony of fine arches and delightful colonnades while enjoying a cool ocean breeze.

Opus incertum: random stones obscuring concrete

Another insight Roman architects obviously had come to is that blank concrete nearly never looks good and weathered concrete absolutely never. Hence they decorated their concrete (opus caementicium) in various ways. Around central Rome marble cladding was used while in the port town of Ostia bricks covered a concrete core. At the Sanctuary of Fortuna stones were randomly pressed into the wet concrete. Opus incertum is ubiquitous at Fortuna Primigenias’s.

The people behind and around the masterpiece

It is no accident that ancient Praeneste developed into a hub of arts and lifestyle in early Rome. Praeneste with its Greco-Etruscan roots (the town was originally not part of Rome, but incorporated in the nascent empire later) benefited from the Roman conquest of her Greek provinces in the 2nd century BC which opened new markets for the merchants of Praeneste. They accumulated enough wealth to finance construction of the vast sanctuary. Money and opportunity also attracted Greek artisans who resettled to Praeneste to be closer to potential patrons, but continued to work in their traditional, Hellenistic styles. They developed a profound influence on art, fashion and taste in Roman society.

Some magnificent artefacts have indeed been unearthed around Palestrina and a good part of those remain on exhibition in the National Museum at Palestrina which is the elegant, semi-circular building that now crowns the leftovers of the old Sanctuary replacing the previous semi-circular colonnade (which you can see in the photos of the Sanctuary model, above). The collection is particularly famous for its display of ‘cistae‘ (photos below), small to medium sized decorated metal boxes that were used by Roman ladies to store jewellery and beauty items like combs and mirrors.

- Hellenistic bust of a Roman matron

- Marble relief of Emperor Trajan and his troops

- Metal ‘cista’ displayed at the National Archaeological Museum of Palestrina

- Delightful handle of a cista displayed at the National Archaeological Museum of Palestrina

- Cista handle figurine at the National Archaeological Museum of Palestrina

Another highlight of the museum collection is the so-called Nile mosaic of Palestrina (photos below). Badly damaged over the centuries, particularly by the Barberini family that ran Palestrina after marrying into the Colonna clan (both were powerful noble families) ripping out, cutting up and partially losing parts of the original Roman floor mosaic in the old forum at the lower end of the Sanctuary (a Roman forum used to be something of a town center containing markets, courts, temples, libraries, squares etc).

Lovingly restored, the large 5 by 5 meter mosaic is an impressive sight again. It depicts the flow of the river Nile from its sources in Ethiopia right across Egypt and into the Mediterranean. Ethiopian hunters, Nile fishermen at work, toga-clad leisure parties, soldiers and temples mingle with a large array of wild beasts to form a colorful and vivid display of exotic Egypt. The mosaic is ancient, estimated to date back to about 100 BC and made up of hundreds of thousands small elements, so-called tesserae.

You find the Nile on the top floor of the museum. Don’t miss it.

- The famous Nile mosaic

- Nile mosaic at the Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia in more detail

- Having a good time at the Nile river; detail from the Palestrina Nile mosaic

- Some of the animals depicted on the Nile mosaic of Palestrina

Praeneste’s treasures strewn

Some of the best pieces found around Palestrina have, however, been moved to more accessible locations. The amazing Braschi Antinous (posing as god Dionysus) was probably found on the grounds of Hadrian’s villa in Palestrina and stands today in the unique collection of the Vatican. Roman lifestyle was, to say the least, permissive. Greek poster boy Antinous was in his days regarded the most handsome man alive – and Hadrian’s special friend 😉 … Apart from that, large, intact statues of Silenus and Emperor Lucius Verus as an athlete found their way from Palestrina to the Vatican museums.

The most famous cista box from Palestrina, the Cista Ficoroni with three argonauts as its handle has been moved to the National Etruscan Museum in Rome.

Good to know:

- Planning: a visit to Palestrina and its National Archaeological Museum is best combined with other adventures, for example a trip to nearby Tivoli with its Villa d’Este water gardens and the vast Villa Adriana

- Timing: set aside about 1 to 2 hours for the museum

- Opening hours: check the museum website (currently daily 09:00 to 20:00)

- Language: most minor displays are in Italian only, but the major ones are bilingual in Italian and English, which is good enough

- Parking: street parking near the museum which is located at N41.840310, E12.892474

- Nuisance alert: museum staff are openly bored and indifferent, and best ignored