A Spiritual Stroll Through Milan

Milan as Italy’s commercial powerhouse, home to its stock exchange and some of the world’s big names in fashion may not sound like the first address in matters of the soul, but scratch a little under the surface and you may discover the unexpected.

But first things first and an admission. My ‘passeggiata spirituale’ did not occur by design, but as the byproduct of hubby’s single-minded insistence “to do important churches in Milan”, no matter how tempting a Saturday sleep-in might have been. Given my, not exaggerating, fascination with the divine beauty of renaissance art I had developed during visits to Florence, Siena and Rome, it did not take much persuasion to give — Milan — ? a try, too.

After dropping the car in a parking lot around Piazza Sempione we walked across the city park towards the Sforza castle before turning right towards – roughly speaking – the area due West of Milan’s iconic ‘duomo’ cathedral. All three destinations of the day, the churches Santa Maria delle Grazie, Basilica di Sant’Ambrogio and San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore are in easy walking distance of each other.

Click this embedded map – Nupur’s Milan Path of Spirituality – to see where you are going.

Santa Maria delle Grazie – reservations only

This UNESCO World Heritage site is mostly not visited in its own right, but just to view Leonardo da Vinci‘s Last Supper. To prevent disappointments make sure that you reserve a ticket for the Last Supper before heading to Santa Maria delle Grazie. There are quotas to regulate the stream of visitors and thereby limit damaging effects on the masterpiece. Chances to snap up a cancelled slot on the spot are meager. Don’t bother trying.

Alas, as we were travelling spontaneously – we had not booked. No Leonardo today.

But where there is shadow … the church actually offers free tours of Santa Maria (without the Cenacolo) every first and third Saturday of the month which provided us some consolation. It includes a guided tour (in English) of the church, the small, but enchanting cloister and – as its highlight – the Bramante Sacristy (the room for preparation of the mass). The latter was commissioned by the then Duke of Milan, Ludovico il Moro who also employed Leonardo to paint the Last Supper in the refectory (the eating room of the Dominican monks who at the time occupied the convent attached to Santa Maria) in the 1490s.

The Bramante Sacristy holds many curious artifacts, like a candle-driven (!) clock which apart from the time shows season and zodiac and a vault ceiling mimicking a deep blue sky dotted with golden stars (incidentally the same pattern that originally adorned the ceiling of Leonardo’s Last Supper room in the refectory – until it was destroyed by allied bombing in 1943). The sacristy cupboards along the sides of the hall are decorated with small but endearing panel paintings from the old (right-hand side) and new (left-hand side) testaments which – as was common in those times – imagine the inhabitants and settings of ancient Israel to look like renaissance Italy’s.

The Bramante Cloister locally known “il chiostro delle rane” for the frog statues (symbolizing metamorphosis) in its center offers a peaceful oasis from the raging crowds waiting around the church precinct for their life-changing Leonardo experience.

- Bramante Cloister at Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

- Ceiling of the Bramante Sacristy at Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

- Apse of the Bramante Sacristy at Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

- Storage boards at the Bramante Sacristy at Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

- Detail of one of the panels at Bramante Sacristy at Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

- Fresco at Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

Basilica di Sant’Ambrogio – serene rigor

The history of this ancient church goes back to the days of the Roman empire. It was first built under the auspices of St. Ambrose between 379 and 386 on the grounds of the former Roman city center which had also been a center of persecution Christians and their martyrdom. The church was re-built in Romanesque style in the 12th century.

Sant’Ambrogio’s visually most attractive feature is probably is its column-lined, perfectly symmetrical portico (front yard) and its hut-shaped facade featuring elegant, arched double loggias. In days gone by the bishops of Milan used to bless worshipers from the upper loggia. Decorative elements are in sparse use. So-called ‘Lombard bands’ – blind, small ornamental arcades – embellish the portico’s arches just under the roof as well as across the facade. Thin stone pilaster strips (low-relief, vertical pillars on a wall) adorn the columns. Apart from that there are irregular inklings of white stones spread across the arches.

The basilica is flanked by two detached bell towers or ‘campaniles’. The thicker, shorter right-hand one stems from the 9th century and was probably used as shelter in times of war. The left campanile was erected in 1144 and extended in the 19th century.

We did of course enter Sant’Ambrogio, but as mass was being celebrated at the time we did not take photos. Which brings us to the issue of opening hours: Mondays to Saturdays you can visit from 7:30 to 12:30 and 14:30 to 19:00 and on Sundays from 7:30 to 13:00 and 15:00 to 20:00. Please keep out during times of religious service.

- Entering the portico of Sant’Ambrogio, Milan

- The portico of Sant’Ambrogio, Milan, on a rainy afternoon

- Sant’Ambrogio, Milan

- Sant’Ambrogio, Milan, from the church end

- The left bell tower at Sant’Ambrogio, Milan

Side note to readers who are familiar with UCLA, Yes, the architectures of Royce Hall and the Powell Library are inspired by Sant’Ambrogio.

San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore – Milan’s crown jewel

Practicalities first. Don’t ask how and why, but this undisputed highlight of the day and absolute must-see in Milan carries no entry fee and even has very convenient opening times on top of that. Miracles do happen, even in Italia. Anyway, it’s open Tuesday to Sunday from 9:30 to 19:30 with extended opening times on Thursdays until 22:30 (closed Mondays, however).

Construction of the current San Maurizio Church began in 1503 replacing a much older house of worship dating back to the 8th or 9th century which in turn was constructed at the site of an ancient Roman circus (racecourse) and reused parts of the city wall built by emperor Maximian whose ruled between 286 and 305. The church was completed in just a few years, although it was not before 1574 that the facade, too, was finalized.

Today, San Maurizio belongs to the few structures that remain of the once vast Monastero Maggiore (major monastery). Because surrounding structures were pulled down and the Corso Magenta opened to traffic the building has suffered structurally and is under constant repair.

Stepping in from the main street, the Corso Magenta, you first enter the so-called “sanctuary” area which in the old days was open to the public for worship. Behind the main altar there is a wall sometimes called the”road screen”. It does not reach up all the way to the ceiling i.e actually does function as a panel to protect the convent area located behind, used by Benedictine nuns until the late 1700s, from prying eyes. While the convent was still in operation, there was no connecting door between the public and convent parts of the church, but where today a painting of the adoration of the magi is placed in the middle of the altar there used to be a grid through which common people on the outside could follow mass being held by the nuns. This is also why the floor of the convent area is about 50 cm above the level of the public, sanctuary area floor.

Click through the gallery below to get an impression of the wonders of artistic achievement that will engulf you upon entering San Maurizio. Nonetheless, you have to experience the rush of color and shape first hand to fully appreciate its near psychedelic effect, especially on the faithful. Love of God has turned into art in this blessed place.

While there is no Michelangelo, Leonardo or divine Raphael on display, local Lombard Renaissance master Bernardino Luini who signs for many of the frescoes at San Maurizio is a worthy match. Other old masters on display are Luini’s sons Aurelio, Giovan Piero and Evangelista Luini, as well as Antonio Campi, Callisto Piazza, Ottavio Semino and Simone Peterzano, the mentor of the great Caravaggio.

The Sanctuary Hall

The frescoes in the hall that used to be open to the public during medieval times are well-documented. You can get a full listing of information either from the detailed Italian Wiki page or from the free, but all too poetic flyers on offer at the volunteers’ desk in the church. Or you simply read the captions in the gallery below which explain some key elements.

- The left side of the non-convent area at San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore, Milan

- San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore, Milan, upper left side of the non-convent area

- Main altar of San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore, Milan

- Ceiling, counterface and three of the four chapels on the right side of the sanctuary of San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore, Milan

- Detail of the Besozzi chapel at San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore, Milan

- Stucco above the Chapel of St. Paul at San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore, Milan

- An allegorical column at San Mauricio al Monastero Maggiore, Milan

- Right-hand, far corner of the public side of San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore, Milan

- San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore, Milan

The Road Screen

The frescoes on the convent-side of the screen wall precede those in the sanctuary area by some thirty years i.e this decorative cycle was the first to be put in place soon after 1509 when the church came into use as a place of worship. While it has so far not been possible to firmly ascribe the various works of art to painters and sponsors, the central fresco of the Eternal Father surrounded by groups of angels playing music, all against a dark blue background dotted with stars is probably the oldest of the lot. Its “retro” style follows the school of Vincenzo Foppa which was influential in the 15th century. It was here, under the eyes of the Godfather, that nuns (mostly from Milan’s nobility) were ordained.

Above and to the sides of the dark, starred area we can admire Bernardino Luini at his best. In their warm, lively colors and soft, delicate designs the figures perfectly realize the ideal of classical beauty. Apart from superbly serene St. Catherine and St. Agatha, Luini presents a passion of Christ series: the Prayer in the Garden, Ecce Homo, Ascent to Calvary and Deposition from the Cross.

- Saints and Angels at San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore, Milan

- The Eternal Father at San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore, Milan

- Bernardino Luini works at the lower level of the convent side of the road screen at San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore, Milan

- Deposition from the cross by Bernardino Luini

- Upper level of the convent side of San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore, Milan

- Detail of the upper level of the convent side of San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore, Milan

The Hall of the Nuns

At the sides of the hall, obscured by a massive wooden choir (where the nuns would meet for prayer and chants) is a relatively plain collection of landscapes which have recently been identified to be restorations dating back to the early 20th century.

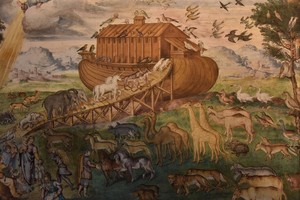

The rear wall of the nuns’ hall is more gripping. It comprises two series, one of scenes from the Old Testament (Noah’s Ark, Original Sin i.e. Adam and Eve and the Sacrifice of Isaac) and the other is a passion of Christ cycle (Capture, Flagellation, Deposition from the Cross and the Last Supper) that mirrors Bernardino Luini’s passion on the opposing wall. All were painted by Bernardino’s sons Giovan Pietro, Evangelista and Aurelio in the second half of the 16th century. Yet while Giovan Pietro and Evangelista followed stylistically in the footsteps of their father, the youngest brother, Aurelio somewhat departed from the Italian renaissance template by paying more attention to detail as common in the Flemish school. Aurelio Luini’s famous depiction of Noah’s ark being boarded by a zoo of animals (photo above) thus stands out in its dynamism and vivacity.

*** *** *** ***

Apologies for the length of this article … once you start getting into things it is hard to stop 😉

Good to know:

- Timing: about 5 hours – we did it in one Saturday afternoon

- Before you go: if you want to see Leonardo da Vincis Last Supper, you need to make a reservation